Why April?

Because, Baseball.

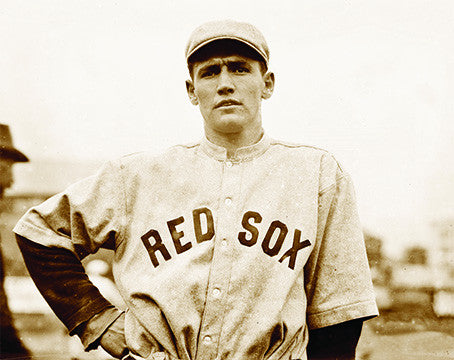

We offer this 1913 baseball card portrait of the Boston Red Sox in honor of one of April’s great gifts. The 117th season of Major League Baseball kicked off on Sunday, April 2. Opening Day offered three games, including one starring the 2016 World Series come-back-kids and champions, the Chicago Cubs. They faced off against the St. Louis Cardinals, who beat them 4-3 in an exciting opening game..

But way back when, “Smoky Joe” Wood was a pitcher who threw a fastball that trailed fire.

“Smoky Joe” Wood

“Smoky Joe” Wood (1889-1985) was born Howard Ellsworth Wood. He got stuck with the name “Joe” because of his parents’ fixation on a circus clown named Joey. In his professional life, people noted that his fastball could make sparks fly, hence the other nickname, “Smoky.”

Wood’s professional career had an unconventional debut. In 1906, his family was living in Ness City, Kansas. Wood noticed a poster announcing a game between the city’s baseball team, the Ness City Nine, and the National Bloomer Girls of Kansas City. As the name suggests, these barnstormers were an all-girl team, but they frequently added boys to the roster. Without hesitation, Wood, 17 at the time, signed on for the game! He helped the Bloomers win the game, 23 to 2, severely trouncing the Ness City Nine. Woods played with the Bloomers for the rest of the summer. He was paid $21 a week.

So Wood was posing as a girl when the Boston Red Sox found him! He joined the team in 1908 at 18 years of age and played with them until 1915. Mostly, he pitched. Wood won 57 games for the Boston Red Sox in 1911 and 1912. 1912 was a particularly stellar year, in which he won 34 games and lost only five. His earned run average (ERA) was 1.91; he struck out 258. No one ever forgot his record that season. Almost 73 years later, his obituary in the New York Times read, “Smoky Joe Wood, Ex-Pitcher, Is Dead; Was 34-5 in 1912.”

In 1917, Wood was sold to the Cleveland Indians. He played with them from 1917 to 1922, mostly as an outfielder. He ended his career with the Indians with a bang, earning his highest hit total for a season with 150. He also set a personal high for runs batted in (RBI) with 92.

Wood died on July 27, 1985, at the age of 95. I hope he died thinking about the two seasons where he dominated professional baseball history. Or maybe he was flashing back to the no-hitter he pitched against the St. Louis Browns on July 29, 1911. Either way, he died as one of baseball’s great men. And in 1995, Smoky Joe made it into the Boston Red Sox Hall of Fame.

Because, Easter

Easter falls on April 16 this year, 2017. Easter Sunday marks the end of Holy Week, the end of Lent, and the last day of Easter. Many people flock to church on this day.

But way back in 1795, there was a special appearance at Christ Church in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on Easter Sunday. President George Washington and his wife Martha were in the crowd.

General Washington at Christ Church, Easter Sunday, 1795

The diaries of George Washington (1732-1799) reveal little about his religious beliefs, although many of his practices were observed by family and acquaintances. We do know that he was brought up in an Anglican household by a mother who favored personal spirituality. This may have influenced the child who became the man who held his beliefs closely to the chest.

Washington was known for his tolerance of the varying religious beliefs of others and worshiped in churches of different denominations. Historians differ on whether Washington attended church regularly or sporadically, but most say that his attendance was more regular during his presidency. He and First Lady Martha Washington usually attended together, although the president was known to frequently leave before she did.

So it is not surprising that George Washington was in church on Easter Sunday, 1795. The date would have been April 5, during the sixth year of his presidency (1789-1797). This 1908 painting by J. L. G. Ferris portrays the president standing beside his coach as Christ Church let out. His wife Martha on his arm, he raises his tricorn hat as others hail him with theirs.

The African American man holding the door of the carriage is probably William Lee (1750-1828), Washington’s favored personal servant. Washington bought Lee when he was a teenager. Lee served Washington at home, was in constant attendance during the Revolutionary War, and worked for him throughout his presidency. Lee is often shown by Washington’s side in paintings. They became very close over the years. He was the only one of Washington’s slaves to be freed outright in Washington’s will.

The church in this painting has sometimes been mistakenly identified as Christ Church in Alexandria, Virginia. Washington actually did attend both by times, but the house of worship painted here is Christ Church in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Christ Church is rich in history. Many other famous folks also attended the church, including Betsy Ross, Benjamin Franklin and his wife Deborah, and many years earlier, William Penn. Both George Washington and his vice president, John Adams, regularly attended the church while presiding over the young country. Seven signers of the Declaration of Independence and five signers of the Constitution also attended and are buried there.

The church is a beloved landmark. This marvelous example of Georgian Colonial architecture, built in 1744, is still standing and in use today. It is located in the Old City neighborhood of Philadelphia between Market and Arch Streets. More than 250,000 visitors visit Christ Church and its burial ground every year.

The artist, J. L. G. (Jean Leon Gerome) Ferris (1863-1930), trained at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. He is most famous for his series of 78 scenes from American history called The Pageant of a Nation.